17

SeptemberGeoArt Second Exhibition

The second GeoArt group exhibition by Ata Tara took place on Friday the 13th of September 2024 at the House of Persia (HOPE) in Melbourne. The exhibition showcased the work of over 30 Iranian artists, both from Australia and Iran, who collaborated alongside musicians to honor the Woman, Life, Freedom movement, celebrating the resilience and strength of Iranian women.

For my contribution, I exhibited nine distinct pieces, each of which is featured in the exhibition brochure. These artworks explored the landscape of Persia, weaving together different narratives to reflect its rich cultural and geographical context. Through my art, I aimed to connect historical, environmental, and contemporary themes to express the profound connection between people and place in Persia.

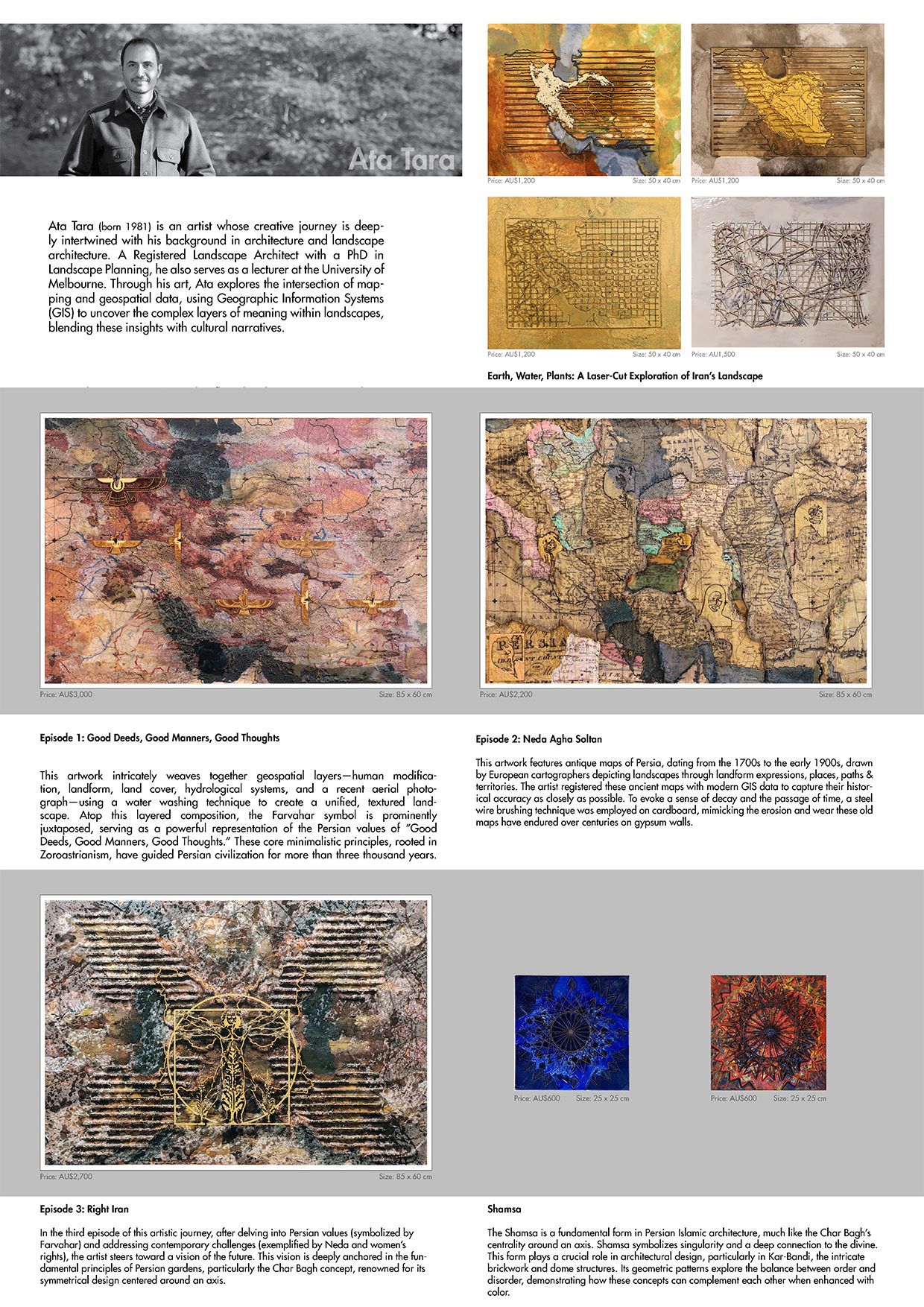

Earth, Water, Plants: A Laser-Cut Exploration of Iran’s Landscape

This series focuses on the essential elements that shape the Iranian landscape: earth, water, and plants. By utilizing laser-cutting techniques, the series intricately renders these elements, offering a tactile representation of Iran’s natural environment.

Earth: The foundation of the series lies in the representation of Iran’s landforms. This is achieved through precise longitudinal and latitudinal sections that reveal the diverse topography of the region. The laser-cut maps capture the undulating terrain, from the rugged mountains to the expansive deserts, providing a tangible sense of the earth’s contours.

Water: The series highlights key hydrological features, with a particular emphasis on the Zayandeh River and the Tigris-Euphrates river systems. These water bodies are layered onto the landform sections, illustrating their vital role in shaping both the physical landscape and the cultural history of the region. The rivers are depicted not just as geographic features, but as lifelines that have nurtured civilizations and sustained ecosystems throughout history.

Plants: Complementing the earth and water elements, the series incorporates representations of Iran’s native vegetation. These plant forms are derived from land cover data and are meticulously integrated into the landscape, emphasizing the connection between flora and the environment. The plants serve as symbols of life and resilience, flourishing in harmony with the earth and water.

Cities: In addition to natural features, the series also addresses the human impact on the landscape by overlaying a network of cities. The population centers are depicted as nodes of influence, their growth and expansion often overshadowing the natural landscape. This aspect of the series prompts viewers to consider the balance between urban development and the preservation of natural spaces.

Three episodes for Iran based on GeoArt theory (narratives of values, challenges/weaknesses & future) were developed for this exhibition:

Episode 1: Good Deeds, Good Manners, Good Thoughts

This artwork intricately weaves together geospatial layers—human modification, landform, land cover, hydrological systems, and a recent aerial photograph—using a water washing technique to create a unified, textured landscape. Atop this layered composition, the Farvahar symbol is prominently juxtaposed, serving as a powerful representation of the Persian values of “Good Deeds, Good Manners, Good Thoughts.” These core minimalistic principles, rooted in Zoroastrianism, have guided Persian civilization for more than three thousand years.

The Farvahar symbol hovers above the landscape, symbolizing the enduring influence of the Persian Empire, whose legacy of inclusivity and cultural richness extends into the present day. The blending of the landscape with modern geopolitical boundaries highlights the shared cultural and ethical values that continue to unite the diverse nations of the region. This artwork invites viewers to reflect on the timeless nature of these values and their relevance in shaping the identity of the region through the ages.

Episode 2: Neda Agha Soltan

This artwork features antique maps of Persia, dating from the 1700s to the early 1900s, drawn by European cartographers depicting landscapes through landform expressions, places, paths & territories. The artist registered these ancient maps with modern GIS data to capture their historical accuracy as closely as possible. To evoke a sense of decay and the passage of time, a steel wire brushing technique was employed on cardboard, mimicking the erosion and wear these old maps have endured over centuries on gypsum walls.

Juxtaposed with these historical maps are laser-cut portraits of Neda Agha Soltan, blended into the composition. This contrast highlights the enduring value of women and their ongoing struggle for a fairer future in the context of ancient Persia. Neda (born 1983) was an Iranian philosophy student who tragically became a symbol of the 2009 presidential protests when she was fatally shot while returning to her car with her music teacher.

The artist, who belongs to the same generation as Neda, poignantly connects the landscape to feminist themes, emphasising the role of women in Iran. This piece also resonates with the recent rise of the “Woman, Life, Freedom” movement, commemorating Neda’s dreams and her hope for a better future for women in Iran. Through this work, the artist calls attention to the ongoing struggle for gender equality in a region steeped in ancient history, yet still facing contemporary challenges.

Episode 3: Right Iran

In the third episode of this artistic journey, after delving into Persian values (symbolized by Farvahar) and addressing contemporary challenges (exemplified by Neda and women’s rights), the artist steers toward a vision of the future. This vision is deeply anchored in the fundamental principles of Persian gardens, particularly the Char Bagh concept, renowned for its symmetrical design centered around an axis.

In this interpretation, however, the entire map of Iran, intricately intertwined with longitudinal sections, is mirrored along two axes to create the iconic Char Bagh layout. This mirrored design evokes the shape of a butterfly, a symbol of transformation and freedom.

The Vitruvian Man, prominently placed in the foreground, symbolizes individualism and humanism—a concept that profoundly influenced European thought during the Renaissance, as captured by Da Vinci. This symbol is complemented by three cypress trees, quintessential elements of Persian gardens, representing the triad of religion, monarchy, and the people/democracy. Together, these elements create a harmonious balance that reflects the Persian ethos prior to the Islamic Revolution, offering a vision of identity and continuity as the country progresses.

The butterfly, shaped by the mirrored map of Iran, embodies a culture ready to rise and flourish, aspiring toward a brighter future. Through this artwork, the artist conveys a message of hope, resilience, and cultural renaissance, championing democratic values while remaining rooted in historical traditions, yet looking forward with optimism and strength.

Shamsa

The Shamsa is a fundamental form in Persian Islamic architecture, much like the Char Bagh’s centrality around an axis. Shamsa symbolizes singularity and a deep connection to the divine. This form plays a crucial role in architectural design, particularly in Kar-Bandi, the intricate brickwork and dome structures. Its geometric patterns explore the balance between order and disorder, demonstrating how these concepts can complement each other when enhanced with color.

In this artwork, the Shamsa’s strong form is emphasized, connecting it with a tradition that transcended borders and spread across the Islamic world, from Andalusia in Spain to India. This graphic and symbolic form unites diverse cultures and languages, highlighting its significance as a visual and spiritual connector throughout the Islamic world.